Could the Salem Witch Trials Happen Again

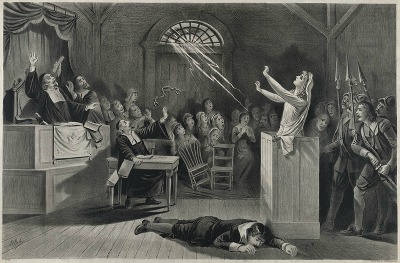

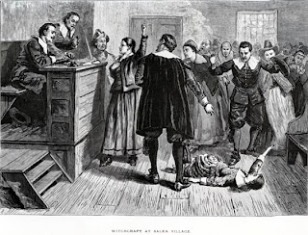

The Salem Witch Trials of 1692 were a dark time in American history. More than 200 people were accused of practicing witchcraft and 20 were killed during the hysteria.

Ever since those dark days ended, the trials have become synonymous with mass hysteria and scapegoating.

The following are some facts about the Salem Witch Trials:

What Were the Salem Witch Trials?

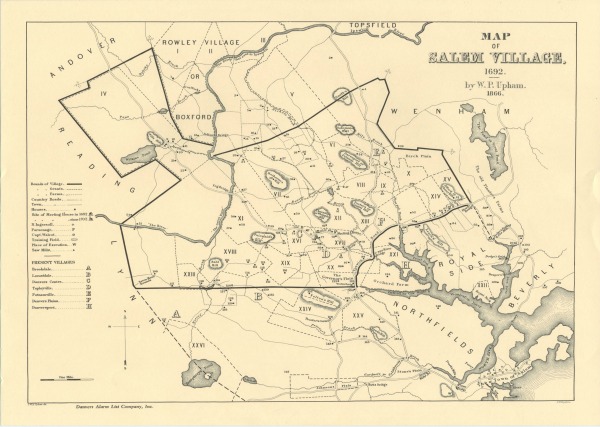

The Salem Witch Trials were a series of witchcraft cases brought before local magistrates in a settlement called Salem which was a part of the Massachusetts Bay colony in the 17th century.

When Did the Salem Witch Trials Take Place?

The Salem Witch Trials officially began in February of 1692, when the afflicted girls accused the first three victims, Tituba, Sarah Good and Sarah Osborne, of witchcraft and ended in May of 1693, when the remaining victims were released from jail.

What Caused the Salem Witch Trials?

The exact cause of the Salem Witch Trials is unknown but they were probably a number of causes. Some of the suggested theories are: conversion disorder, epilepsy, ergot poisoning, Encephalitis, Lyme disease, unusually cold weather, factionalism, socio-economic hardships, family rivalries and fraud.

Also, In 17th century Massachusetts, people often feared that the Devil was constantly trying to find ways to infiltrate and destroy Christians and their communities.

As a devout and strongly religious community living in near isolation in the mysterious New World, the community of Salem had a heightened sense of fear of the Devil and, as a result, it didn't take much to convince the villagers that there was evil among them.

In addition to this constant sense of fear, Salem residents were also under a great deal of stress during this period due to a number of factors.

One major factor was that in 1684, King Charles II revoked the Massachusetts Bay Colony's royal charter, a legal document granting the colonists permission to colonize the area.

The charter was revoked because the colonists had violated several of the charter's rules, which included basing laws on religious beliefs and discriminating against Anglicans.

A newer, more anti-religious charter replaced the original one in 1691 and also combined the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Plymouth Colony and several other colonies into one.

The puritans, who had left England due to religious persecution, feared their religion was under attack again and worried they were losing control of their colony. The political instability and threat to their religion created a feeling of uneasiness and discontent in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Other factors included a recent small pox epidemic in the colony, growing rivalries between families within the colony, a constant threat of attack from nearby Native-American tribes, and a recent influx of refugees trying to escape King William's war with France in Canada and New York.

Events of the Salem Witch Trials:

The witchcraft hysteria in Salem first began in January of 1692 when a group of young girls, who later came to be known as the "afflicted girls," fell ill after playing a fortune-telling game and began behaving strangely.

Afflicted Girls:

Elizabeth Booth

Elizabeth Hubbard

Mercy Lewis

Betty Parris

Ann Putnam, Jr.

Susannah Sheldon

Abigail Williams

Mary Walcott

Mary Warren

The first of the girls to start experiencing symptoms was Betty Parris, followed by Abigail Williams, Ann Putnam Jr., Mary Walcott and Mercy Lewis.

Shortly after, Elizabeth Hubbard, Susannah Sheldon, Mary Warren and Elizabeth Booth all started to experience the same symptoms, which consisted of suffering "fits," hiding under furniture, contorting in pain and experiencing fever.

Many modern theories suggest the girls were suffering from epilepsy, boredom, child abuse, mental illness or even a disease brought on by eating rye infected with fungus.

In February, Samuel Parris called for a doctor, who is believed to be Dr. William Griggs, to examine the girls. The doctor was unable to find anything physically wrong with them and suggested they may be bewitched.

Shortly after, two of the girls named the women they believed were bewitching them. These women were Sarah Good, Sarah Osburn and a slave named Tituba who worked for Reverend Samuel Parris.

These three women were social outcasts and easy targets for the accusation of witchcraft. It was not difficult for the people of Salem to believe they were involved in witchcraft.

On March 1st, Tituba, Sarah Good and Sarah Osburn were arrested and examined. During Tituba's examination, she made a shocking confession that she had been approached by Satan, along with Sarah Good and Sarah Osburn, and they had all agreed to do his bidding as witches.

Tituba's confession was the trigger that sparked the mass hysteria and the hunt for more witches in Salem. It also silenced any opposition to the idea that the Devil had infiltrated Salem.

That same month, four more women were accused and arrested:

Rebecca Nurse

Martha Corey

Dorothy Good

Rachel Clinton (from Ipswich)

Although the afflicted girls were the main accusers during the trials, many historians believe the girl's parents, particularly Thomas Putnam and Reverend Samuel Parris, were egging the girls on and encouraging them to accuse specific people in the community that they didn't like in an act of revenge.

In April, more women were accused, as well as a number of men:

Sarah Cloyce

Elizabeth Proctor

John Proctor

Giles Corey

Abigail Hobbs

Deliverance Hobbs

William Hobbs

Mary Warren

Bridget Bishop

Sarah Wildes

Nehemiah Abbott Jr.

Mary Easty

Edward Bishop

Sarah Bishop

Mary English

Phillip English

Reverend George Burroughs

Lydia Dustin

Susannah Martin

Dorcas Hoar

Sarah Morey

In May, as the number of cases grew, Governor William Phips set up a special court, known as the Court of Oyer and Terminer (which translate to "hear and determine") to hear the cases. This was a special type of court in English law established specifically to hear cases that are extraordinary and serious in nature.

This court consisted of eight judges. In June, Nathaniel Saltonstall resigned and was replaced by Jonathan Corwin.

Court of Oyer and Terminer Judges:

Jonathan Corwin

Bartholomew Gedney

John Hathorne

John Richards

William Stoughton, Chief Magistrate

Samuel Sewall

Nathaniel Saltonstall

Peter Sergeant

Waitstill Winthrop

The number of people accused and arrested in May surged to over 30 people:

Sarah Dustin

Ann Sears

Arthur Abbott

Bethiah Carter Sr

Bethiah Carter Jr

Mary Witheridge

George Jacobs Sr

Margaret Jacobs

Rebecca Jacobs

John Willard

Alice Parker

Ann Pudeator

Abigail Soames

Sarah Buckely

Elizabeth Colson

Elizabeth Hart

Thomas Farrar Sr

Roger Toothaker

Mary Toothaker

Margaret Toothaker

Sarah Proctor

Mary DeRich

Sarah Bassett

Susannah Roots

Elizabeth Cary

Sarah Pease

Martha Carrier

Elizabeth Fosdick

Wilmot Redd

Elizabeth Howe

Sarah Rice

John Alden Jr

William Proctor

John Flood

Arrest warrants were issued for George Jacobs Jr. and Daniel Andrews but they evaded arrest.

Although the witch hunt started in Salem Village, it quickly spread to the neighboring towns, including Amesbury, Andover, Salisbury, Topsfield, Ipswich and Gloucester, and numerous residents of those towns were brought to Salem and put on trial.

The number of accusations and arrests began to decline in June but still continued and soon the local jails held more than 200 accused witches.

Due to overcrowding in the jails, the accused witches were kept in multiple jails in Salem town, Ipswich and Boston.

The Salem jail was located at the corner of Federal Street and St. Peter Street. The jail was a small wooden structure with a dungeon underneath.

Since the accused witches were considered dangerous prisoners, they were kept in the dungeon and were chained to the walls because jail officials believed this would prevent their spirits from fleeing the jail and tormenting their victims.

In 1813, the wooden structure of the jail was remodeled into a Victorian home and in 1956 the home was razed. A large brick building now stands on this spot with a memorial plaque dedicated to the old jail.

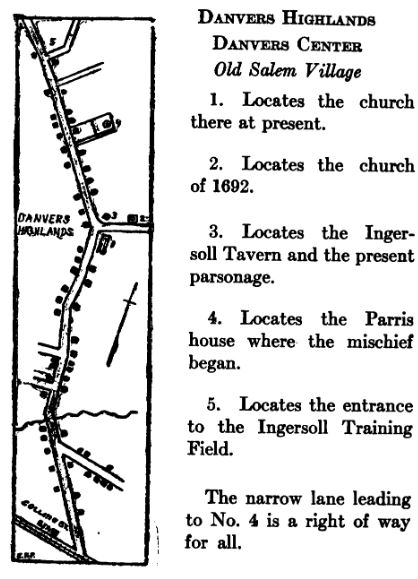

Pre-trial examinations were held at the Salem Village meetinghouse, in Reverend Samuel Parris' house in Salem Village, in Ingersoll Tavern at Salem Village and in Beadle's Tavern in Salem Town.

There the accused were questioned by a judge in front of a jury, which decided whether or not to indict the accused on charges of witchcraft. If the accused was indicted, they were not allowed a lawyer and they had to decide to plead guilty or not guilty with no legal counsel to guide them.

Early Opposition to the Salem Witch Trials:

Another interesting fact about the witch trials is not everyone in Salem actually believed in witchcraft or supported the trials. There were many critics of the witch hunt, such as a local farmer John Proctor, who scoffed at the idea of witchcraft in Salem and called the young girls scam artists.

Critics such as Proctor were quickly accused of witchcraft themselves, under the assumption that anyone who denied the existence of witches or defended the accused must be one of them, and were brought to trial. Proctor's entire family was accused, including all of his children, his pregnant wife Elizabeth, and sister-in-law.

The Trials:

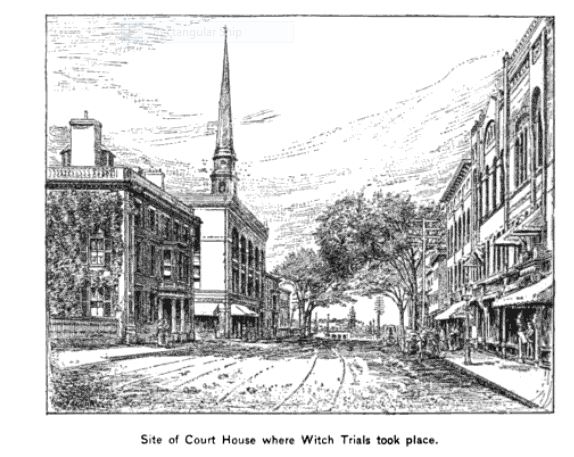

The trials were held in the Salem courthouse, which was located in the center of Washington Street about 100 feet south of Lynde Street, opposite of where the Masonic Temple now stands. The courthouse was torn down in 1760 but a plaque dedicated to the courthouse can still be seen today on the wall of the Masonic Temple on Washington Street.

Bridget Bishop was the first person brought to trial. Bishop had been accused of witchcraft years before but was cleared of the crime.

Bridget was accused by five of the afflicted girls, Abigail Williams, Ann Putnam Jr., Mercy Lewis, Mary Walcott and Elizabeth Hubbard, who stated she had physically hurt them and tried to make them sign a pact with the devil.

During her trial, Bishop repeatedly defended herself, stating "I am innocent, I know nothing of it, I have done no witchcraft …. I am as innocent as the child unborn…"

The Salem Witch Trials Executions:

Bridget Bishop was convicted at the end of her trial and sentenced to death. She was hanged on June 10, 1692 at a place now called Proctor's Ledge, which is a small hill near Gallows Hill, making her the first official victim of the witch trials.

Five more people were hanged in July, one of which was Rebecca Nurse. Rebecca Nurse's execution was a pivotal moment in the Salem Witch Trials.

Although many of the other accused women were unpopular social outcasts, Nurse was a pious, well-respected and well-loved member of the community.

When Nurse was first arrested, many members of the community signed a petition asking for her release. Although she wasn't released, most people were confident she would be found not guilty and released.

Her initial verdict was, in fact, not guilty, but upon hearing the verdict the afflicted girls began to have fits in the courtroom. Judge Stoughton asked the jury to reconsider their verdict. A week later, the jury changed their minds and declared Nurse guilty.

After Nurse's execution on July 19th, the residents of Salem started to seriously question the validity of the trials.

On July 23, John Proctor wrote to the clergy in Boston. He knew the clergy did not fully approve of the witch hunts. Proctor told them about the torture inflicted on the accused and asked that the trials be moved to Boston where he felt he would get a fair trial.

The clergy later held a meeting, on August 1, to discuss the trials but were not able to help Proctor before his execution. Proctor's wife managed to escape execution because she was pregnant, but Proctor was hanged on August 19 along with five other people.

Another notable person who was accused of witchcraft was Captain John Alden Jr., the son of the Mayflower crew member John Alden.

Alden was accused of witchcraft by a child during a trip to Salem while he was on his way home to Boston from Canada. Alden spent 15 weeks in jail before friends helped break him out and he escaped to New York. He was later exonerated.

Yet another crucial moment during the Salem Witch Trials was the public torture and death of Giles Corey. Corey was accused of witchcraft in April during his wife's examination. Knowing that if he was convicted his large estate would be confiscated and wouldn't be passed down to his children, Corey brought his trial to a halt by refusing to enter a plea.

English law at the time dictated that anyone who refused to enter a plea could be tortured in an attempt to force a plea out of them. This legal tactic was known as "peine forte et dure" which means "strong and harsh punishment."

The torture consisted of laying the prisoner on the ground, naked, with a board placed on top of him. Heavy stones were loaded onto the board and the weight was gradually increased until the prison either entered a plea or died.

In mid-September, Corey was tortured this way for three days in a field near Howard Street until he finally died on September 19. His death was gruesome and cruel and strengthened the growing opposition to the Salem Witch Trials.

As the trials and executions continued, colonists began to doubt that so many people could actually be guilty of this crime. They feared many innocent people were being executed. Local clergymen began speaking out against the witch hunt and tried to persuade officials to stop the trials.

How Did the Salem Witch Trials End?

Around the end of September, the use of spectral evidence was finally declared inadmissible, thus marking the beginning of the end of the Salem Witch Trials.

Although spectral evidence, evidence based on dreams and visions, wasn't the only evidence used in court during the Salem Witch Trails, it was the most common evidence and the easiest evidence for accusers to fake.

Other evidence used in the trials included confessions of the accused, possession of certain items such as poppets, ointments or books on the occult, as well as the presence of an alleged "witch's teat," which was a strange mole or blemish, on the accused person's body.

On September 22, eight people were hanged. These were the last hangings of the Salem Witch Trials.

On October 29, Phips dismissed the Court of Oyer and Terminer. The 52 remaining people in jail were tried in a new court, the Superior Court of Judicature, the following winter.

The new court was presided over by William Stoughton, Thomas Danforth, John Richards, Waitstill Winthrop and Samuel Sewall. Now that spectral evidence was not allowed, most of the remaining prisoners were found not guilty or released due to a lack of real evidence.

Those who were found guilty were pardoned by Governor Phips. The governor released the last few prisoners the following May.

Salem Witch Trial Victims:

A total of 19 accused witches were hanged at Proctor's Ledge, near Gallows Hill, during the witch trials.

The others were either found guilty but pardoned, found not guilty, were never indicted or simply evaded arrest or escaped from jail.

Found Guilty and Executed:

Bridget Bishop (June 10, 1692)

Sarah Good (July 19, 1692)

Elizabeth Howe (July 19, 1692)

Susannah Martin (July 19, 1692)

Rebecca Nurse (July 19, 1692)

Sarah Wildes (July 19, 1692)

George Burroughs (August 19, 1692)

Martha Carrier (August 19, 1692)

John Willard (August 19, 1692)

George Jacobs, Sr (August 19, 1692)

John Proctor (August 19, 1692)

Alice Parker (September 22, 1692)

Mary Parker (September 22, 1692)

Ann Pudeator (September 22, 1692)

Wilmot Redd (September 22, 1692)

Margaret Scott (September 22, 1692)

Samuel Wardwell (September 22, 1692)

Martha Corey (September 22, 1692)

Mary Easty (September 22, 1692)

Refused to enter a plea and tortured to death:

Giles Corey (September 19th, 1692)

Found Guilty and Pardoned:

Elizabeth Proctor

Abigail Faulkner Sr

Mary Post

Sarah Wardwell

Elizabeth Johnson Jr

Dorcas Hoar

Pled Guilty and Pardoned:

Rebecca Eames

Abigail Hobbs

Mary Lacy Sr

Mary Osgood

Died in Prison:

Sarah Osburn

Roger Toothaker

Ann Foster

Lydia Dustin

Escaped from Prison:

John Alden Jr.

Edward Bishop Jr.

Sarah Bishop

Mary Bradbury

William Barker Sr.

Andrew Carrier

Katherine Cary

Phillip English

Mary English

Edward Farrington

Never Indicted:

Sarah Bassett

Mary Black

Bethiah Carter, Jr

Bethiah Carter, Sr

Sarah Cloyce

Elizabeth Hart

William Hobbs

Thomas Farrer, Sr

William Proctor

Sarah Proctor

Susannah Roots

Ann Sears

Tituba

Evaded Arrest:

George Jacobs Jr

Daniel Andrews

Other victims include two dogs who were shot or killed after being suspected of witchcraft.

It's a common myth that the Salem Witch Trials victims were burned at the stake. The fact is, no accused witches were burned at the stake in Salem, Massachusetts. Salem was ruled by English law at the time, which only allowed death by burning to be used against men who committed high treason and only after they had been hanged, quartered and drawn.

As for why these victims were targeted in the first place, historians have noted that many of the accused were wealthy and held different religious beliefs than their accusers.

This, coupled with the fact that the accused also had their estates confiscated if they were convicted has led many historians to believe that religious feuds and property disputes played a big part in the witch trials.

Life After the Salem Witch Trials:

Daily chores, business matters and other activities were neglected during the chaos of the witch trials, causing many problems in the colony for years to come, according to the book The Witchcraft of Salem Village:

"The whole colony, moreover, had suffered. The people had been so determined upon hunting out and destroying witches that they had neglected everything else. Planting, cultivating, the care of houses, barns, roads, fences, were all forgotten. As a direct result, food became scarce and taxes higher. Farms were mortgaged or sold, first to pay prison fees, then to pay taxes; frequently they were abandoned. Salem Village began that slow decay which eventually erased its houses and walls, but never its name and memory."

As the years went by, the colonists felt ashamed and remorseful for what had happened during the Salem Witch Trials. Since the witch trials ended, the colony also began to suffer many misfortunes such as droughts, crop failures, smallpox outbreaks and Native-American attacks and many began to wonder if God was punishing them for their mistake.

On December 17, 1697, Governor Stoughton issued a proclamation in hopes of making amends with God. The proclamation suggested that there should be:

"observed a Day of Prayer with Fasting throughout the Province…So that all God's people may put away that which hath stirred God's Holy jealousy against his land; that he would…help us wherein we have done amiss to do so no more; and especially that whatever mistakes on either hand have fallen into…referring to the late tragedy, raised among us by Satan and his instruments, through the awful judgement of God, he would humble us therefore and pardon all the errors and people that desire to love his name…"

The day of prayer and fasting was held on January 15, 1698, and was known as the Day of Official Humiliation. On that day, Judge Samuel Sewall attended prayer services at Boston's South Church and asked Reverend Samuel Willard to read a public apology that Sewall had written, which states:

"Samuel Sewall, sensible of the reiterated strokes of God upon himself and family; and being sensible, that as to the guilt contracted upon the opening of the late Commission of Oyer and Terminer at Salem (to which the order of this day relates) he is, upon many accounts, more concerned than any that he knows of, desires to take the blame and shame of it, asking pardon of men, and especially desiring prayers that God, who has an unlimited authority, would pardon that sin and all other his sins; personal and relative: And according to his infinite benignity and sovereignty, not visit the sin of him, or of any other, upon himself or any of his, nor upon the land: But that he would powerfully defend him against all temptations to sin, for the future; and vouchsafe him the efficacious, saving conduct of his word and spirit."

In 1706, afflicted girl Ann Putnam, Jr., also issued a public apology for her role in the Salem Witch Trials, particularly in the case against her neighbor Rebecca Nurse. Her apology states:

"I desire to be humbled before God for that sad and humbling providence that befell my father's family in the year about '92; that I, then being in my childhood, should, by such a providence of God, be made an instrument for the accusing of several persons of a grievous crime, whereby their lives were taken away from them, whom now I have just grounds and good reason to believe they were innocent persons; and that it was a great delusion of Satan that deceived me in that sad time, whereby I justly fear I have been instrumental, with others, though ignorantly and unwittingly, to bring upon myself and this land the guilt of innocent blood; though what was said or done by me against any person I can truly and uprightly say, before God and man, I did it not out of any anger, malice, or ill-will to any person, for I had no such thing against one of them; but what I did was ignorantly, being deluded by Satan. And particularly, as I was a chief instrument of accusing of Goodwife Nurse and her two sisters, I desire to lie in the dust, and to be humbled for it, in that I was a cause, with others, of so sad a calamity to them and their families; for which cause I desire to lie in the dust, and earnestly beg forgiveness of God, and from all those unto whom I have given just cause of sorrow and offence, whose relations were taken away or accused."

In 1711, the colony passed a bill restoring some of the names of the convicted witches and paid a total of £600 in restitution to their heirs. Since some families of the victims did not want their family member listed, not every victim was named.

The bill cleared the names of: George Burroughs, John Proctor, George Jacobs, John Willard, Giles Corey, Martha Corey, Rebecca Nurse, Sarah Good, Elizabeth Howe, Mary Easty, Sarah Wildes, Abigail Hobbs, Samuel Wardwell, Mary Parker, Martha Carrier, Abigail Faulkner, Anne Foster, Rebecca Eames, Mary Post, Mary Lacey, Mary Bradbury and Dorcas Hoar.

Since some of the law enforcement involved in the Salem Witch Trials were being sued by some of the surviving victims, the bill also stated: "no sheriff, constable, goaler or other officer shall be liable to any prosecution in the law for anything they then legally did in the execution of their respective offices."

In 1957, the state of Massachusetts officially apologized for the Salem Witch Trials and cleared the name of some of the remaining victims not listed in the 1711 law, stating: "One Ann Pudeator and certain other persons" yet did not list the other victim's names.

In November of 1991, Salem town officials announced plans for a Salem Witch Trials Memorial in Salem. At the announcement ceremony, playwright Arthur Miller made a speech and read from the last act of his 1953 play, The Crucible, which was inspired by the Salem Witch Trials.

In August of 1992, on the 300th anniversary of the trials, the Salem Witch Trials Memorial was unveiled and dedicated by Nobel Laureate Eli Wiesel.

On October 31, 2001, the state amended the 1957 apology and cleared the names of the remaining unnamed victims, stating:

"Chapter 145 of the resolves of 1957 is hereby amended by striking out, in line 1, the words 'One Ann Pudeator and certain other persons' and inserting in place thereof the following words:- Ann Pudeator, Bridget Bishop, Susannah Martin, Alice Parker, Margaret Scott and Wilmot Redd."

In January of 2016, the site where the Salem Witch Trials hangings took place was officially identified as Proctor's Ledge, which is a small wooded area in between Proctor Street and Pope Street in Salem.

In 2017, on the 325th anniversary of the Salem Witch Trials, the newly built Proctor's Ledge Memorial was unveiled at the base of the ledge on Pope Street.

Primary Sources of the Salem Witch Trials:

Everything we know now about the trials comes from just a handful of primary sources of the Salem Witch Trials. In addition to official court records there are also several books written by the ministers and other people involved in the trials:

♦ A Brief and True Narrative of Some Remarkable Passages Relating to Sundry Persons Afflicted by Witchcraft, at Salem Village: Which happened from the Nineteenth of March, to the Fifth of April, 1692 by Deodat Lawson circa 1692

♦ The Wonders of the Invisible World: Being an Account of the Tryals of Several Witches Lately Executed in New-England by Cotton Mather circa 1692

♦ More Wonders of the Invisible World by Robert Calef circa 1700

♦ A Modest Enquiry Into the Nature of Witchcraft by John Hale circa 1702

If these individuals had never written these books or helped record the proceedings, we wouldn't know half of what we know about the witch trials.

If you want to learn more about the Salem Witch Trials, check out this article on the best Salem Witch Trials books.

Sources:

Upham, Charles W. Salem Witchcraft: With an Account of Salem Village and a History of Opinions on Witchcraft. Wiggin and Lunt, 1867.

Crewe, Sabrina and Michael V. Uschan. The Salem Witch Trials. Gareth Stevens Publishing, 2005

Upham, Charles Wentworth. Salem Witchcraft and Cotton Mather: A Reply. Morrisiana, 1869

Jackson, Shirley. The Witchcraft of Salem Village. Random House, 1956

Fowler, Samuel Page. An Account of the Life, Character, & C., of the Rev. Samuel Parris of Salem Village. William Ives and George W. Pease, 1857

"Session Laws." The 190th General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, www.malegislature.gov/Laws/SessionLaws/Acts/2001/Chapter122

"The 1692 Salem Witch Trials." The Salem Witch Museum, www.salemwitchmuseum.com/education/salem-witch-trials

Blumberg, Jess. "A Brief History of the Salem Witch Trials." Smithsonian Magazine, Smithsonian Institute, 23 Oct. 2007, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/a-brief-history-of-the-salem-witch-trials-175162489/

gonzaleshavemprought.blogspot.com

Source: https://historyofmassachusetts.org/the-salem-witch-trials/

0 Response to "Could the Salem Witch Trials Happen Again"

Post a Comment